In a world drenched in the mundane and the mechanical, anthropomorphism beckons us toward a more enchanted reality. It dares us to assign human characteristics to the non-human entities around us, yielding a curious tapestry woven from threads of imagination and insight. This proclivity to endow animals, plants, and even inanimate objects with human traits is not merely a whimsical pastime; it serves profound purposes across cultures, disciplines, and narratives.

Anthropomorphism, derived from the Greek words “anthropos” meaning human, and “morphe” meaning form, transcends simple imagination. It is a cognitive phenomenon that allows us to bridge the chasm separating humanity from the natural world. From children’s literature to corporate branding, the implications and manifestations of anthropomorphism are ubiquitous.

The Cultural Resonance of Anthropomorphism

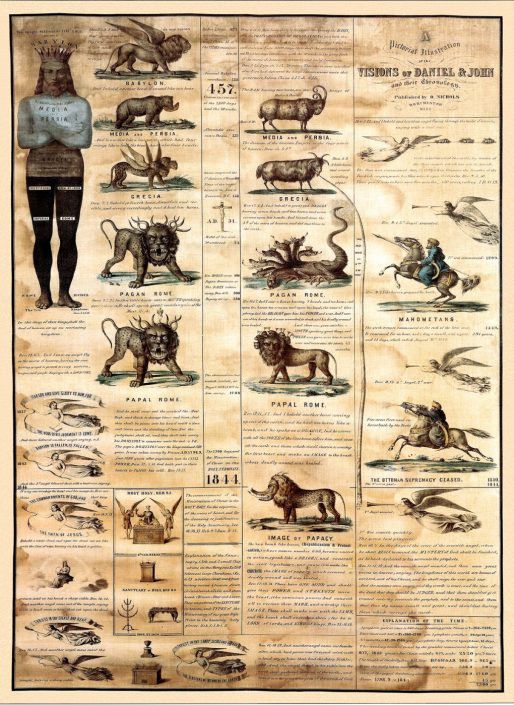

Across myriad cultures and epochs, the practice of attributing human characteristics to non-human entities has painted the canvases of myths, folklore, and religious narratives. Indigenous tribes often infuse nature with sacred traits, perceiving animals as custodians of wisdom—guardians of human morality and spiritual guidance. The coyote in Native American folklore, often depicted as a trickster, illustrates the blurring of the line between human folly and animal instinct, revealing the complexities of both states of being in an intricate, allegorical dance.

In contrast, Western literature has long embraced anthropomorphism as a narrative device that breathes life into the pages of storytelling. From Aesop’s Fables, where creatures embody human virtues and vices, to modern animated films where animals embark on epic quests, the device serves to reflect societal truths and nurture empathy. When a character like Shrek, a disgruntled ogre, exhibits traits of vulnerability or resilience, audiences are invited to introspectively engage with their own experiences and emotions.

The Psychological Underpinnings

The allure of anthropomorphism can also be depicted through a psychological lens. Cognitive scientists suggest that this phenomenon arises from our innate desire to connect and empathize. It allows individuals to process complex emotions and navigate moral dilemmas by drawing parallels between human experiences and those of other beings. For example, when we see a forlorn dog waiting at a shelter, our brains instinctively ascribe feelings of sadness and longing, prompting us to rescue and comfort.

This anthropocentric tendency has been harnessed in fields such as marketing and branding, where companies utilize anthropomorphized characters to create rapport with audiences. The iconic Geico Gecko, with its charming accent and witty banter, transforms a mundane insurance service into an approachable, relatable entity. By imbuing a seemingly faceless corporation with personality, consumers develop emotional connections that transcend transactional relationships.

Anthropomorphism in Art and Literature

Throughout history, artists have harnessed anthropomorphism to explore the depths of human emotion and social commentary. In the realm of visual arts, Frida Kahlo’s surreal portrayals often infuse elements of her identity into flora and fauna, rendering them as mirrors reflecting her own human struggles and triumphs. The imaginative landscapes not only breathe life into her canvases but also allow viewers to confront their own narratives through an unconventional portrayal of existence.

In literature, classic works like George Orwell’s “Animal Farm” masterfully exploit anthropomorphism to critique political ideologies. By depicting farm animals with intricate personality traits and aspirations, Orwell creates an allegorical resonance that challenges readers to scrutinize the machinations of power and governance. The simplicity of the story belies layered insights into human nature, revealing the darkness that can lurk within the soul.

The Ethical Dimensions

While anthropomorphism weaves enchanting narratives, it also raises ethical questions. The act of infusing non-human entities with human traits can lead to misconceptions about their behavior and ecological roles. For instance, portraying wolves as villainous creatures can endanger their conservation, as society may neglect their critical ecological roles in maintaining wildlife balance. When humans project their motivations onto the animal kingdom, the consequences may ripple through ecosystems, distorting the intricate web of life.

Additionally, anthropomorphism raises important discussions around animal welfare. An understanding that animals experience emotions, albeit differently from humans, can foster empathetic attitudes toward their treatment. It prompts us to reflect on our obligations as stewards of the environment—imploring us not to extend humanlike traits indiscriminately, but to appreciate the distinctiveness of each being.

Conclusion: A Shared Existence

Ultimately, anthropomorphism invites us into a realm where the human and non-human coexist in a delicate dance of understanding and emotion. Through this lens, we reshape our perception of the world, nurturing empathy and forging connections that might otherwise remain dormant. By embracing the kaleidoscopic array of life surrounding us, we foster a deeper appreciation for the myriad behaviors, emotions, and experiences that inhabit our shared cosmos.

In the colorful tapestry of existence, anthropomorphism serves as a bridge, beckoning us to relate, engage, and ultimately, to reflect upon the profound interconnectedness that defines the human experience, urging us to perceive the world not just for its tangible elements but for the stories it tells through the shared heartbeat of life.