Have you ever found yourself wondering whether your pet truly understands your emotions, or perhaps experienced that strange moment when an inanimate object seemed to beckon your affection? The phenomenon of anthropomorphism plays an intriguing role in our psychological experiences and extends to the realm of theory of mind and attribution. This exploration of anthropomorphism unravels its layers and challenges our perceptions of consciousness and agency.

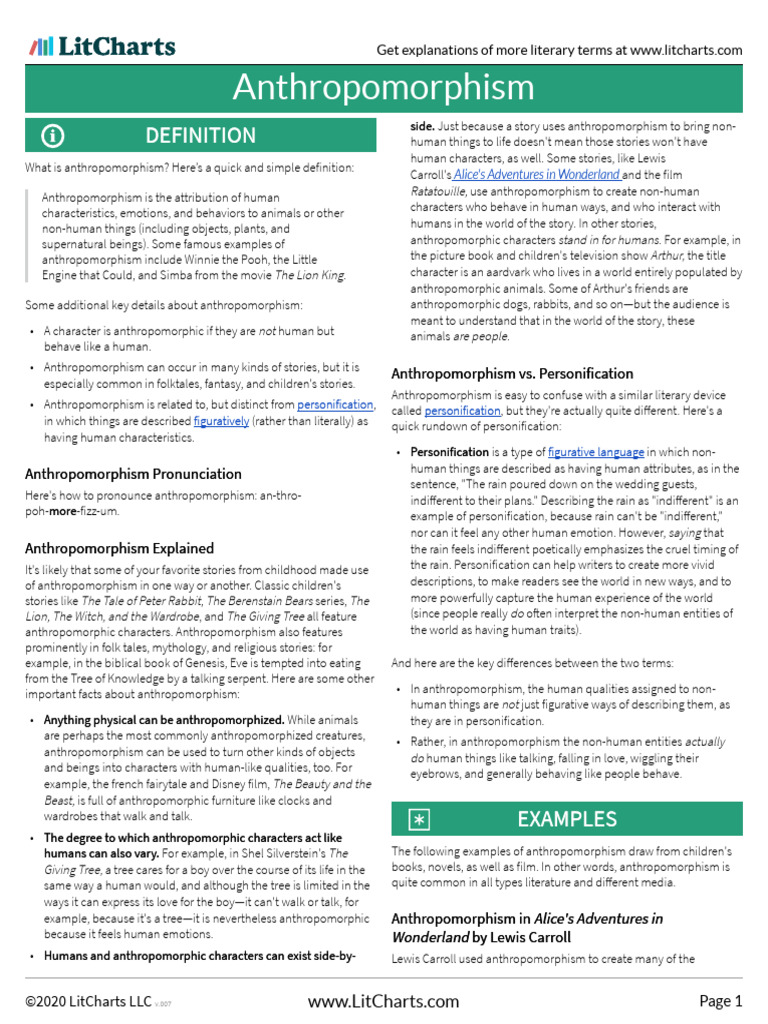

To commence, it is essential to delineate what anthropomorphism entails. Anthropomorphism refers to the attribution of human traits, emotions, or intentions to non-human entities. This can range from the whimsical—like depicting dogs as philosophers pondering life’s mysteries—to the more insidious, such as attributing malicious intent to a malfunctioning piece of technology. It calls into question whether our instincts to humanize the world around us stem from a cognitive necessity or a reflection of our emotions.

At the core of anthropomorphism lies the concept of theory of mind, which is our ability to attribute mental states—beliefs, intents, desires, emotions—to ourselves and others. Humans possess an innate talent for dizzyingly complex social interactions, often requiring the capability to perceive the emotional landscapes of those around them. But where does this ability extend? Can non-human entities, like animals or robots, possess a semblance of a mind? Or are we merely projecting our human experiences onto them?

This inquiry blooms into deeper philosophical questions. For instance, consider the imaginary dialogue you might have with your pet while sharing a quiet evening at home. In this moment, do you genuinely believe your cat understands your feelings, or are you nurturing a fantasy that embodies your lonely heart? Such reflections suggest a psychological mechanism at play whereby we evoke theory of mind to establish bonds with those we interact with.

Anthropomorphism can also serve an adaptive purpose. In human evolution, fostering empathy and understanding was essential for communal survival. By attributing human traits to animals or objects, our ancestors could better anticipate and respond to their behaviors. For instance, a predatory animal perceived as cunning and malevolent would prompt more cautious actions from its human observer. This anticipatory empathy not only allowed for survival but also fostered connections that transcended species boundaries.

But let’s pivot to a playful challenge. Imagine a world where we elevate this tendency towards anthropomorphism into the realm of artificial intelligence. As machines become increasingly sophisticated—able to adapt, learn, and even mimic human emotions—do we begin attributing a conscious experience to them? The creation of lifelike robots raises a pressing question: to what extent should we extend our theory of mind to these beings? Is it illusion, or might we genuinely coexist and engage in meaningful relationships with entities devoid of true consciousness?

This conversation leads to the intersection of attribution theory, which delves into how individuals interpret actions and behaviors, assigning motives behind them. The challenge arises when we consider whether the attributions we make regarding these non-human entities are justified. If a robot assists you in daily tasks and responds to your needs, do you finally recognize it as a partner rather than a mere tool? Attribution becomes particularly fascinating when we find ourselves unable to disentangle intention from action in these situations.

As we unpack motivational attribution, we also uncover aspects of our relationship with nature. Many people derive enjoyment from anthropomorphizing nature itself—imagining forests whispering secrets, rivers as symbols of life force, or storms as divine communication. This inclination not only fosters a profound appreciation for the environment but also highlights the potent psychological benefits of engaging with the natural world. In this context, anthropomorphism emerges as a key to understanding our interconnectedness with all forms of life.

The implications of anthropomorphism extend into education and empathy enhancement, particularly among children. When children engage with anthropomorphized characters—from the friendly cartoon bear to fantastical talking plants—they are not just entertained; they learn compassion, social skills, and emotional intelligence. The challenge, then, is ensuring that such portrayals maintain fidelity to reality, so as not to instill misconceptions about the boundaries of human and non-human perspectives.

As we navigate through the intricacies of anthropomorphism, we confront the ethical considerations it presents. Ascribing human qualities to non-human entities can lead to alarming consequences if those entities, such as advanced AI, are deemed deserving of rights or ethical treatment. The question emerges: Should a robot that displays emotions warrant moral consideration, or should it remain a mere reflection of our own emotional projections?

In conclusion, anthropomorphism encapsulates a world rich with interpretations and implications. It sits at the crossroads of cognitive psychology, philosophy, and ethics, allowing us to explore the nature of consciousness while inviting us to forge connections within an ever-expanding universe of beings. Through this lens, we open ourselves to deeper understanding—stimulating curiosity about our interactions with those we once deemed separate from us. Embracing the complexities of anthropomorphism beckons us not merely to question the intent of others—human or otherwise—but to genuinely engage with the essence of existence itself. As we ponder this, we must ask: what stories do we choose to tell about the world around us, and why do they matter?