Anthropomorphism, the attribution of human traits, emotions, and intentions to non-human entities, is a phenomenon deeply entrenched in our cognitive framework. The implications of this tendency extend beyond whimsy and literature; they infiltrate our interactions with technology, animals, and even inanimate objects. But is it merely a cognitive mistake, or could anthropomorphism serve a more profound purpose?

To embark on this inquiry, one must first ponder the whimsical but urgent question: Is it foolish to envision the world through a human lens? Can ascribing human-like qualities to non-human actors actually provide a richer understanding of reality? This exploration invites the reader to traverse the realms of psychology, philosophy, and even artificial intelligence.

Anthropomorphism manifests in various contexts. From childhood stories where animals converse and express desires, to contemporary AI assistants that simulate conversation and companionship, this cognitive bias appears omnipresent. But one must confront the potential pitfalls of anthropomorphism. When do these imaginings stray into the territory of error? And when might they illuminate the nuances of our experiences?

The root of anthropomorphism lies in our innate desire for connection. We are inherently social beings, hardwired to seek relationships and derive meaning from interaction. This desire might explain why we project emotions onto pets, finding solace and understanding in a companion that listens—albeit without judgment. Whether it’s the cat curled up on your lap or the dog wagging its tail at your arrival, these moments embody the human spirit motivated by empathy.

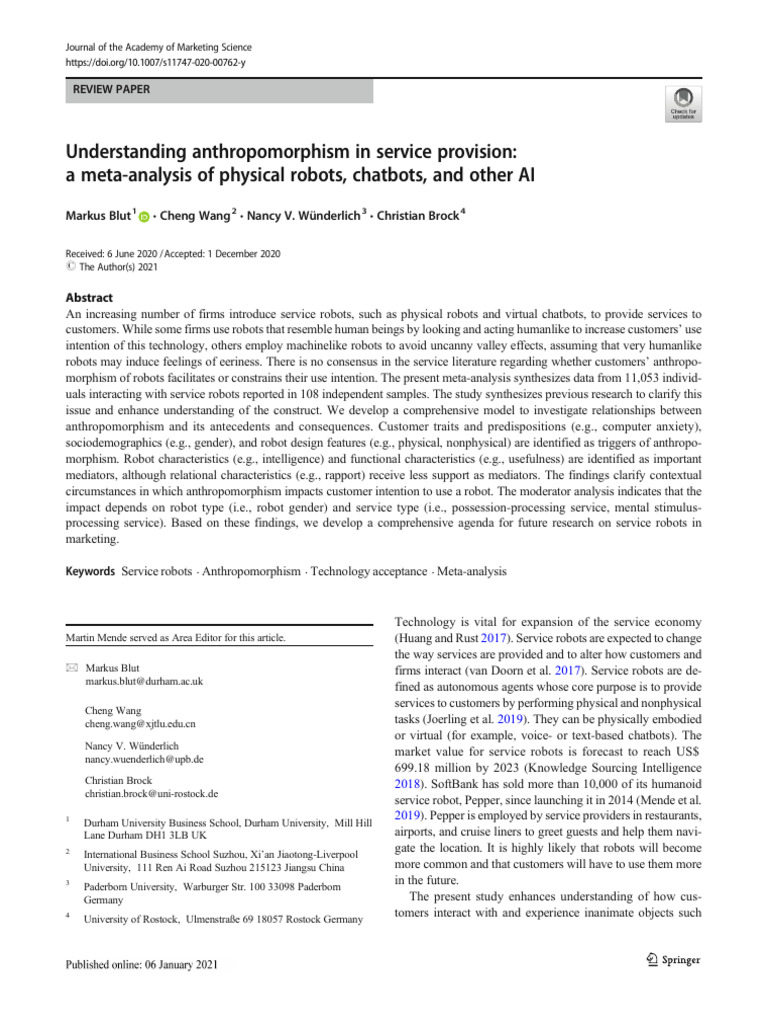

However, psychological research suggests anthropomorphism is also riddled with pitfalls. For instance, significant decisions made under the illusion of machine sentience can result in detrimental consequences. When farmers interact with autonomous tractors as though they have agency, the fine line between human-like qualities and mechanistic capabilities blurs. This emergency of misunderstanding could lead to complacency and, ultimately, operational failure. This begs the question: Are we elevating our machines to a status that they are unprepared to handle while neglecting our responsibility to comprehend their limitations?

Yet, one must also consider the counterargument that anthropomorphism can indeed foster deeper relationships and enhance learning. Emotional connections can facilitate empathy, leading to greater motivation in scenarios ranging from education to environmental conservation. Imagine a child who is taught the importance of conservation through the story of a bear that pleads for help to save its habitat. The motivational pull of anthropomorphism could inspire a generation more attuned to environmental challenges, promoting action in contexts where sterile facts might falter.

Turning to the realm of artificial intelligence, the implications of anthropomorphic tendencies grow exponentially. With AI, we are presented with a particularly challenging scenario. While machines don’t possess emotions or consciousness, their design suggests interpersonal relationships, portraying simulated emotions through dialogue and responsiveness. This phenomenon raises critical questions: Do we unintentionally dilute the essence of human relationships by fostering bonds with machines? Or perhaps using anthropomorphism as a bridge to understanding technology enhances our interaction with a rapidly evolving digital landscape.

Notably, the creative industries have long leveraged anthropomorphism as a narrative device. In the broader context of storytelling, characters that embody both human and non-human traits resonate with audiences, evoking empathy and engagement. Think of Disney’s “Toy Story,” where toys come to life with rich emotional tapestries. By humanizing inanimate objects, storytellers invite audiences to explore complex themes of identity, purpose, and belonging. Hence, anthropomorphism serves not only as a cognitive phenomenon but as a foundational pillar of narrative construction, shaping cultural dialogues and societal norms.

As individuals navigate various domains, the significance of context becomes paramount. The application of anthropomorphism in children’s education, emotional connection with pets, and engagement with machines can be potent tools for fostering understanding and connectivity. Yet, each domain carries its own risks; in some, the tendency can lead to misunderstanding, manipulation, or complacency. Therefore, should we engage in a cognitive re-evaluation of our anthropomorphic tendencies?

Tackling this cognitive bias through a critical lens necessitates an amalgamation of skepticism and awareness. Could we cultivate an appreciation for the non-human world without superimposing our emotions onto it? And could this clearer distinction help refine relationships with technology, nature, and even one another? Perhaps a dual approach that embraces anthropomorphism for its emotional richness while recognizing its limitations would serve us best.

In essence, the question of whether anthropomorphism is truly a cognitive mistake or a social construct with utility reveals a nuanced landscape rich with contradictions. It poses a playful challenge, compelling us to rethink not just our understanding of non-human entities, but the very nature of our existence. As we navigate the bounds of our imagination and cognition, the interplay between our human experiences and the non-human world deepens, offering a kaleidoscope of insights and opportunities for growth.

Ultimately, we stand at the crossroads of understanding, tasked with wielding the delicate balance between imagination and reality. Engaging with the world through our anthropomorphic lens could illuminate profound truths while presenting challenges that invite thoughtful discourse. It invites contemplation: should we cherish it as an indelible facet of human cognition, or temper its reach to preserve the integrity of our relationships with the world around us?