Anthropomorphism, a fascinating cognitive phenomenon, manifests as the attribution of human traits, emotions, and intentions to non-human entities, particularly animals and inanimate objects. This intriguing attribute not only enriches storytelling across various media but also plays a pivotal role in our psychological landscape. As we delve into the depths of psychological anthropomorphism, one cannot help but pose a thought-provoking question: what if our inherent propensity to perceive the world through a human lens is both a boon and a bane? Could this inclination to anthropomorphize actually distort our understanding of nature and reality?

To unravel this conundrum, it is essential to explore the intricate web of psychological anthropomorphism. This term encapsulates the nuanced ways in which human psychology influences our interpretation of the actions and personalities of non-human entities. At its core, psychological anthropomorphism stems from a deep-seated desire for connection. Humans, being inherently social creatures, crave interaction and empathy. When faced with unfamiliar beings or objects, it is natural to project our feelings and experiences onto them. This fundamental trait can be traced back to childhood, where imagination reigns supreme, and stuffed animals serve as confidants, imbued with lives, thoughts, and feelings far beyond their fabric and stuffing.

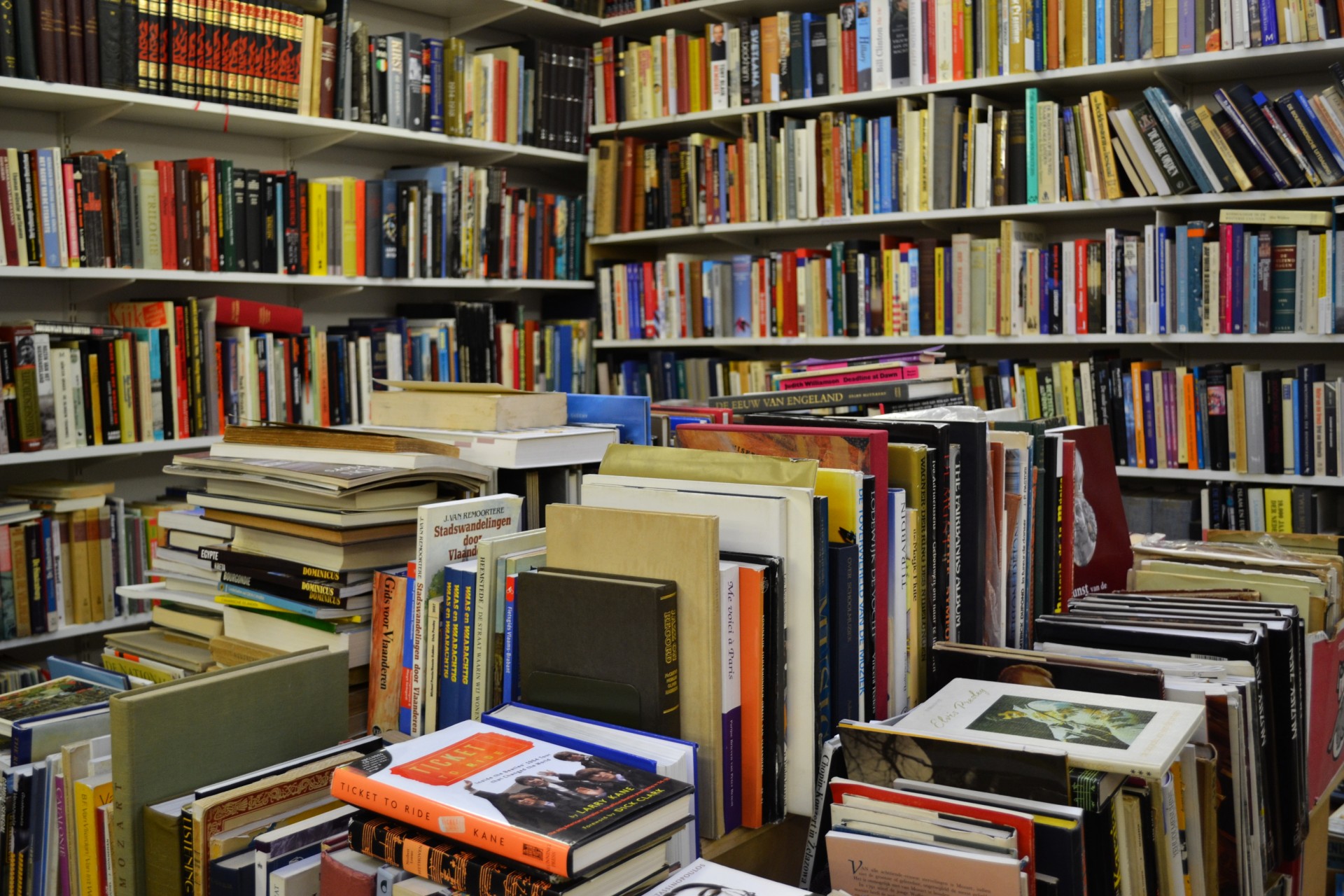

As this tendency evolves, it transcends mere playfulness. In literature, for instance, anthropomorphism enables readers to associate emotionally with characters that are not intrinsically human. Consider classic works such as George Orwell’s “Animal Farm,” which employs anthropomorphic characters to explore complex sociopolitical themes. Through the lens of pig leadership and the foolishness of sheep, Orwell invites readers to grapple with the moral failings of society. The emotional weight borne by these creatures underscores how anthropomorphism can comment on human nature by presenting it in a more approachable, digestible form.

Moreover, in modern media, psychological anthropomorphism takes on new dimensions. Films like Pixar’s “Inside Out” exemplify this phenomenon brilliantly. By giving emotions like Joy, Sadness, and Anger distinct personalities, the filmmakers enable audiences to engage with complex psychological concepts. Viewers readily empathize with these tangible representations of human feelings, fostering a deeper understanding of emotional processing. This shows that anthropomorphism is not just a literary device but a critical mechanism for conveying profound ideas and emotions.

Yet, while anthropomorphism can foster empathy and understanding, it also poses challenges. Could our propensity to attribute human-like qualities to non-human entities lead to misconceptions? This is particularly evident in the realm of environmental psychology, where anthropomorphism can shape our relationship with nature. On one hand, seeing animals or ecosystems as sentient beings may inspire compassion and a desire to protect them. This was notably seen during campaigns advocating for animal rights and conservation efforts, where portraying animals as relatable entities elicits emotional responses from the public.

However, this same tendency can backfire. When we anthropomorphize animals such as elephants or dolphins, we might overlook the complexity of their actual needs and behaviors. Assuming they think and feel as humans do can lead to misguided conservation strategies that fail to address the true essence of their existence. This raises an important challenge: how can we balance empathy and accuracy in our relationships with the non-human world? Striking this balance is crucial in fostering sustainable practices that genuinely benefit both humans and the ecosystems we inhabit.

Furthermore, in our increasingly technological society, anthropomorphism has seeped into our interactions with artificial intelligence and robotics. As technology evolves, devices are becoming more sophisticated and lifelike, capable of mimicking human communication and emotions. Many users naturally respond to these interactions with empathy, projecting human traits onto machines designed for utility. This phenomenon, often termed social robots or companion robots, raises significant ethical questions. If we perceive a robot as a companion, what are the implications for our ability to form genuine human relationships? Does reliance on anthropomorphized technology compromise our emotional intelligence and interpersonal skills?

Compounding this dilemma is the commercialization of anthropomorphism. Marketing strategies frequently exploit our innate tendency to anthropomorphize to forge connections between consumers and products. From animated mascots like Tony the Tiger to the friendly demeanor of a children’s cereal, companies leverage the allure of human-like attributes to establish brand loyalty. This phenomenon calls into question the authenticity of our choices. Are we drawn to these products because of genuine value, or merely because we project human emotions and experiences onto them?

As we navigate the intricate layers of psychological anthropomorphism, it becomes abundantly clear that our relationship with the non-human world, whether through literature, environmental conservation, or technology, requires a careful examination. Embracing the capacity to relate empathetically is vital, yet it is equally crucial to remain vigilant against the distortions that anthropomorphism may evoke. In this era defined by rapid innovation and ongoing ecological crises, striking a balance between empathy and reality is imperative.

In conclusion, while anthropomorphism enriches our emotional landscapes and deepens our understanding, it presents significant challenges that must not be ignored. As we ponder the consequences of our tendency to imbue non-human entities with human characteristics, we must ask ourselves: how can we cultivate a relationship with the world that acknowledges both our need for connection and the intrinsic nature of the beings we encounter? By critically examining these questions, we develop a more nuanced approach to our interactions with both the familiar and the unknown, ultimately fostering a more harmonious coexistence.