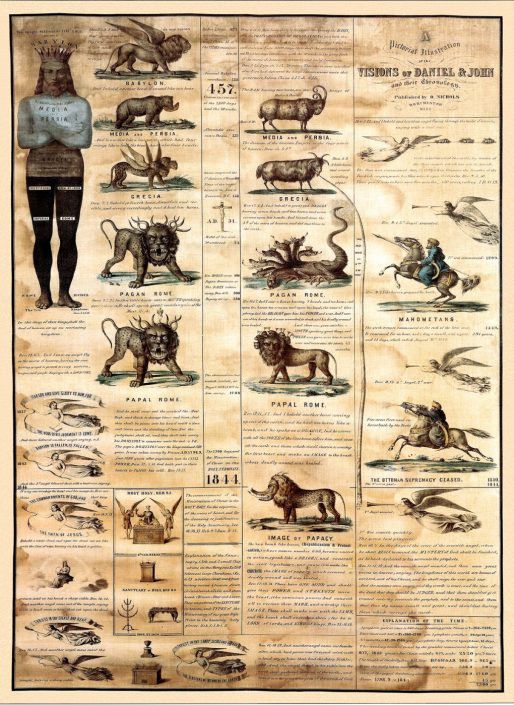

Anthropomorphism—a term derived from ancient Greek meaning “to give human form or attributes to entities that are not human”—permeates both our daily lives and the broader cultural consciousness. Its ubiquity invites consideration, spurring an inquiry into the cognitive biases that underpin our tendency to imbue non-human entities with human-like characteristics. This innate proclivity reveals not merely a whimsical fascination but also deeper psychological motivations correlating with our understanding of the world and our place within it.

Imagine a household pet exhibiting traits of loyalty and remorse. While the observable behaviors might be interpreted through an anthropomorphic lens—envisioning the dog’s tail wagging and ears flattening as feelings akin to human emotions—such interpretations may also mask a more profound psychological phenomenon. This inclination to attribute human qualities to animals, inanimate objects, or even artificial intelligence is not merely a quirk; it reflects foundational cognitive biases that shape our interactions, understanding, and emotional responses to the world.

At the core of anthropomorphism lies a significant cognitive bias known as the “gambler’s fallacy.” This bias manifests when we expect a non-human entity to behave in a certain way based on sporadic encounters or outcomes. For instance, a person might interpret a pet’s behavior—like catching a frisbee—or a robot’s complex response in a social environment as indicative of intelligence or understanding, even when such behaviors do not warrant such assumptions. This tendency can skew our understanding of animal instincts, machine learning, and even the emotional intelligence of non-human entities.

Another relevant cognitive bias is the “illusion of control.” When individuals anthropomorphize, they often believe they have greater mastery over events or entities than they actually do. This can lead to an overreliance on pets for companionship, as well as misplaced trust in technology. When humans ascribe intentions to their devices, believing their smartphone or smart home assistant possesses an understanding of their needs, they may misinterpret the limits of artificial intelligence and automation. This can create a paradoxical dependence on technology that grows increasingly complex, even as the actual technological capabilities remain static.

In social contexts, anthropomorphism serves as a tool for emotional regulation. By projecting human traits onto non-human entities, individuals can navigate their feelings more comfortably. For example, a parent may portray a stuffed animal as a friend to foster a child’s empathy. Similarly, marketing strategies often leverage this bias, enculturating consumers to feel emotional attachments to brands or products by personifying their mascots or endorsements. These personified characters, embedded with relatable emotions and narratives, create powerful connections that influence consumer behavior more effectively than typical advertising techniques.

From an evolutionary perspective, the inclination toward anthropomorphism may reflect an adaptive function. Our ancestors thrived by recognizing patterns and forming social bonds, whether with fellow humans or other living beings. This proclivity for recognizing agency, even in non-human entities, may have heightened their survival instincts. Consequently, interpreting ambiguous stimuli—like animal tracks in the wilderness—as indicative of an approaching predator showcases our ability to read intent where none may exist. This cognitive strategy may have conferred considerable advantages, allowing early humans to navigate risks with greater efficiency.

Despite the advantages, this cognitive bias is not without its pitfalls. Anthropomorphism can lead to misjudgments that result in ecological harm or dangerous human-animal interactions. For instance, the inclination to treat wild animals as if they were domesticated pets—imbuing them with human characteristics—is fraught with danger. Such distorted perceptions can lead to both imprudent interactions and undermine important conservation efforts, as people might fail to appreciate the innate behaviors and instincts that drive wildlife.

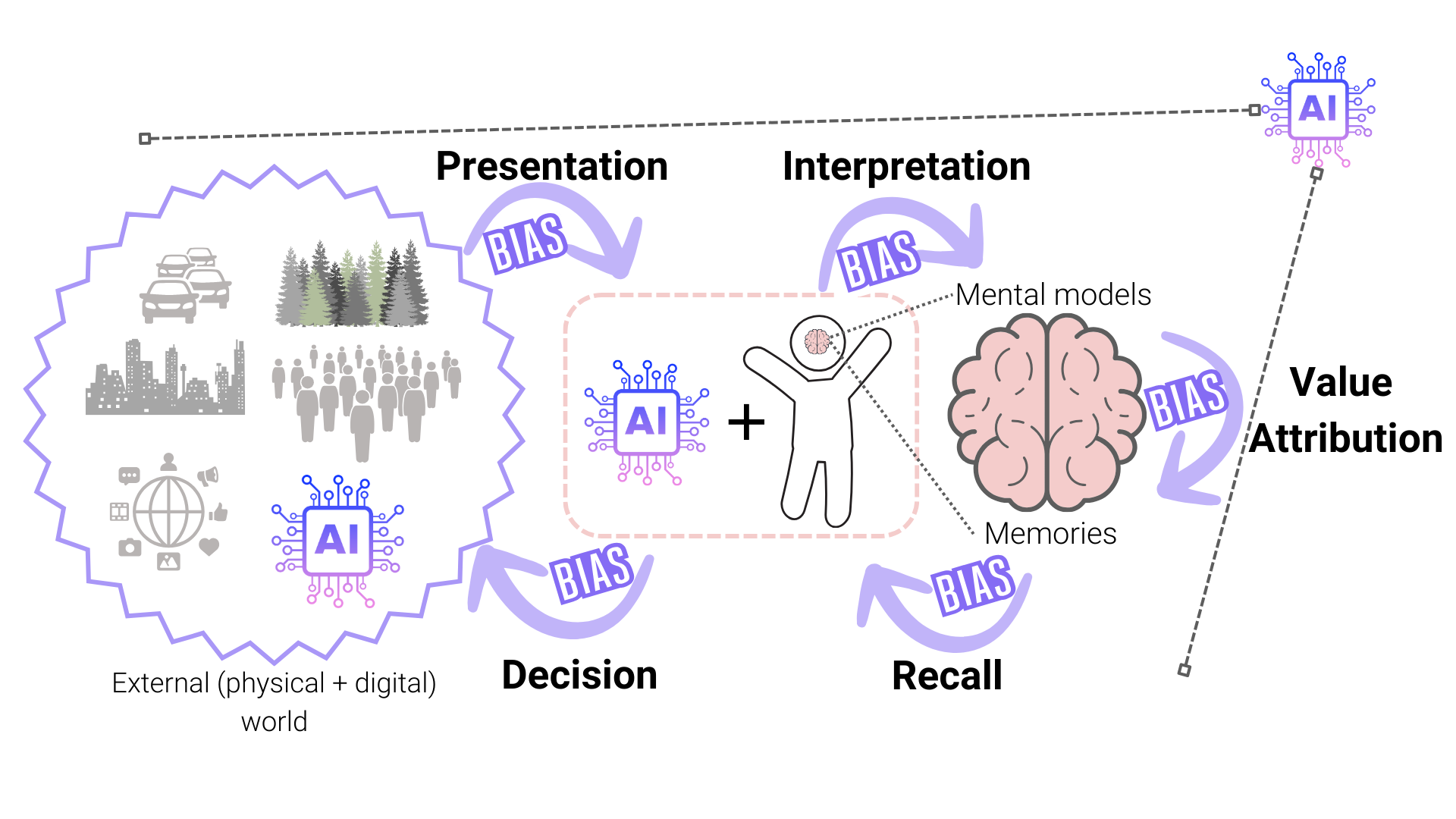

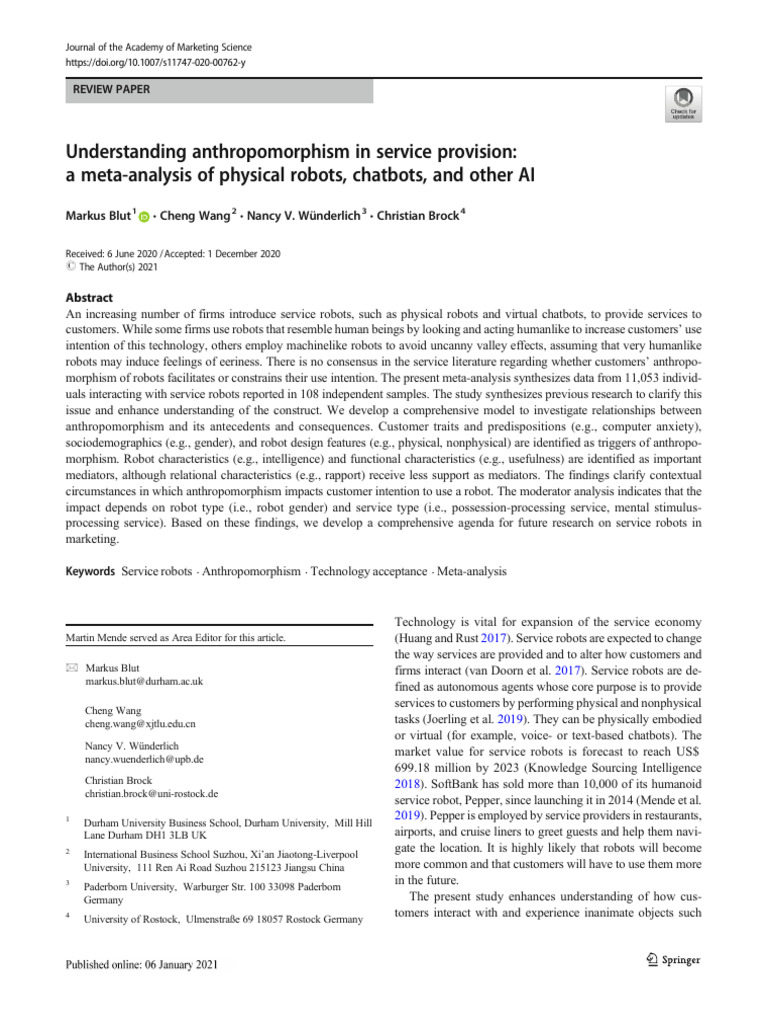

In the technological realm, anthropomorphism is even more pronounced. As artificial intelligence continues to flourish, human-like representations contribute to a growing phenomenon termed the “Eliza effect.” This effect occurs when individuals interact with machines, mistaking their programmed responses for genuine understanding or emotional insight. As chatbots become increasingly human-like in their communication, users may inadvertently dismiss the underlying algorithms that propel these digital interactions, often attributing empathy and awareness where none exist. Such misunderstandings can foster unrealistic expectations, potentially leading to disappointment or mistrust when these systems fail to deliver on their anthropomorphic promises.

This brings us to the ethical implications of anthropomorphism, especially as we advance further into a digital age punctuated by artificial intelligence. Society must grapple with the challenges of anthropomorphized technology, forging frameworks to ensure ethical interactions. As individuals navigate these blurred lines between human and machine, fostering awareness around cognitive biases becomes essential in preventing misguided attributions and unrealistic expectations. We must acknowledge that while anthropomorphism enriches our interactions with the world around us, it can also distort our perceptions and relationships.

In conclusion, anthropomorphism is not merely a fascinating quirk of human cognition but a lens through which to understand our psychological urges and biases. Our tendency to ascribe human-like traits to non-human entities reflects deeper motivations tied to emotional comforts, social bonding, and survival instincts. In navigating an increasingly complex world imbued with anthropomorphized technology and characters, it is incumbent upon us to cultivate awareness of the cognitive biases that influence our perceptions. By doing so, we can foster more authentic relationships—whether with a beloved pet, a revered animal, or an intelligent machine—grounded in the reality of their true nature, rather than an embellished understanding shaped by our own cognitive whims. This journey towards clarity is not just enlightening; it is essential for engaging meaningfully with the intricate tapestry of life that envelops us.