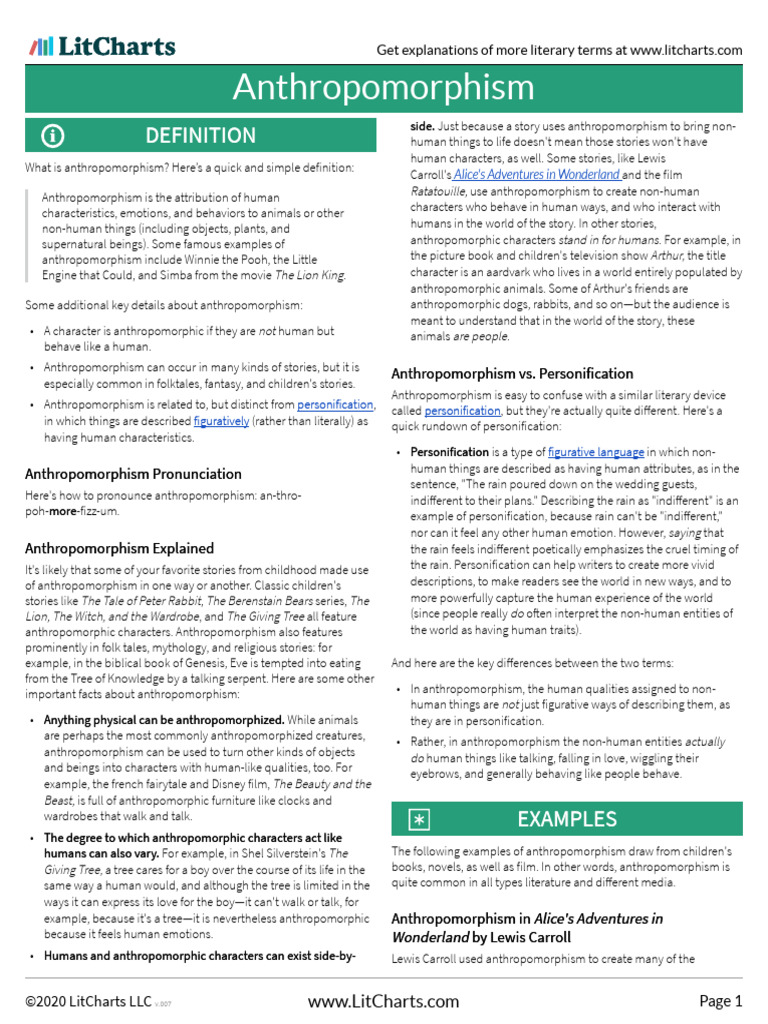

Throughout the annals of human thought, anthropomorphism, the artistic and contemplative practice of attributing human characteristics to non-human entities, has carved a unique niche in both philosophy and folklore. This intricate dance between the human imagination and the natural world has shaped our understanding of the universe, infusing ordinary objects, animals, and even abstract concepts with a vibrancy that transcends mere representation. From ancient mythologies to modern storytelling, anthropomorphic thought has evolved, revealing not only our enduring need for connection but also the underlying complexities of human consciousness.

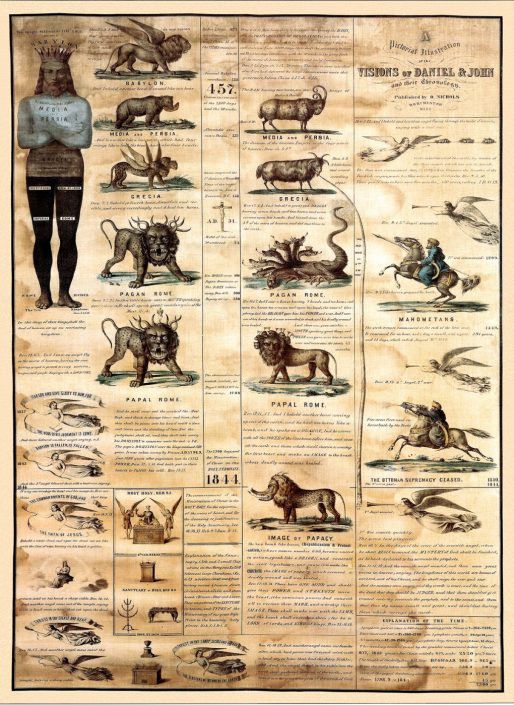

The genesis of anthropomorphic thought can be traced back to prehistoric societies, where animism reigned supreme. Early humans likely perceived the world around them as alive with spirits. Trees whispered secrets, rivers beckoned with gentle murmurs, and mountains towered as sentinels over the landscape. In such ethereal imaginings, animals were not merely beasts of burden but relatives in a vast family of existence. This close kinship served as a foundation for early myths, where gods embodied the traits of creatures that walked the earth. Thus, anthropomorphism burgeoned as a vehicle for understanding and narrating the complexities of existence.

With the rise of organized religions in antiquity, anthropomorphic traits were imbued in deities, imbuing them with human emotions, desires, and failings. Take, for example, the pantheon of Greek mythology. Gods such as Zeus and Hera were far more than omnipotent beings; their jealousies, romances, and rivalries mirrored the very fabric of human life. This anthropomorphic portrayal allowed ancient peoples to relate to these divine figures, using their stories as both cautionary tales and guiding principles for moral conduct.

The philosophical inquiries of the classical era further refined our understanding of anthropomorphism. Thinkers such as Aristotle grappled with the relationship between humans and nature, proposing that the world was a hierarchically structured entity, where man reigned supreme. The anthropocentric gaze became more pronounced, with nature viewed through a human lens, fostering a sense of dominion but also distancing humanity from the intrinsic sanctity of the natural world. This perception would burgeon into the Age of Enlightenment, which heralded a pivotal shift in anthropomorphic thought.

During the Enlightenment, the nexus between anthropomorphism and rationalism became ever more pronounced. Philosophers like René Descartes famously posited that animals were mere automata, devoid of reasoning or emotion. This radical reductionist view contradicted the earlier associations of animals with human traits, propagating a mechanistic worldview that dismissed emotional connections with non-human entities. Yet, this very negation planted the seeds for a new wave of anthropomorphic exploration, aligning itself with the burgeoning Romantic movement that followed.

The Romantic era reinstated an emotional resonance with nature, leading to a renaissance of anthropomorphic expressions in literature and art. William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, figures synonymous with Romantic poetry, infused their works with the essence of nature as sentient and alive. The “Lyrical Ballads” became a conduit for expressing the sublime, where the mountains were rough-hewn guardians, and the rivers, flowing with wisdom and sorrow, echoed the human experience. This resurgence highlighted a pivotal shift in anthropomorphic thought: it transformed from mere representation into a profound exploration of identity and belonging.

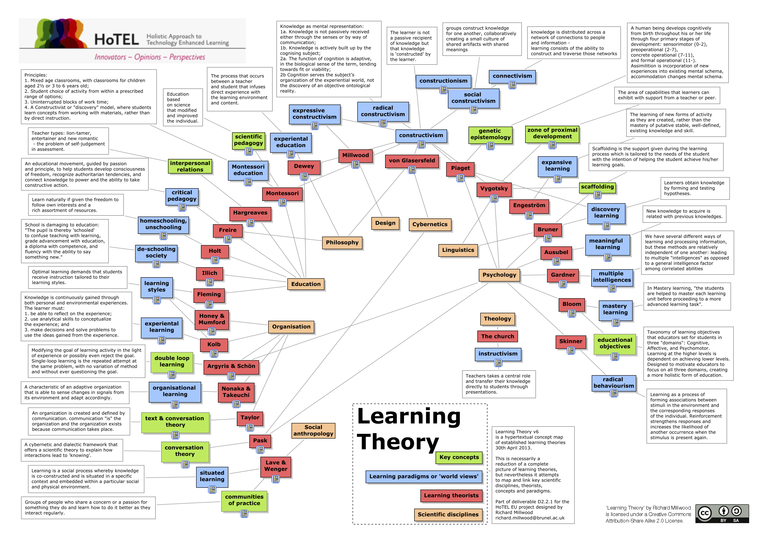

As societies approached the modern era, anthropomorphism found a fertile substratum in the burgeoning fields of psychology and cognitive science. Sigmund Freud’s interpretations invited deeper reflection on the projection of human emotions and desires onto the non-human, positing that such tendencies stem from unconscious drives. This perspective opened an avenue to examine how anthropomorphic thought serves as a mechanism for individuals to grapple with their existential dilemmas, facilitating a connection to the otherwise inscrutable universe.

In recent decades, anthropomorphism has continued to captivate scholars, artists, and thinkers alike. The emergence of technology and synthetic intelligence has incited anew anthropomorphic impulses, as digital companions and AI systems are imbued with human-like qualities. This phenomenon raises poignant questions about our relationship with technology; are we simply reflecting our own characteristics onto these creations, or do they represent a nascent hybrid identity? Such inquiries propel anthropomorphism into contemporary discourse, challenging traditional boundaries and reshaping our understanding of consciousness itself.

Interestingly, the allure of anthropomorphism extends beyond highbrow thought, permeating popular culture and the realms of advertising and media. Animation, in particular, has embraced this artistic device, with characters like Mickey Mouse and Shrek resonating on deeply emotional levels with audiences. These anthropomorphized figures evoke laughter, empathy, and even introspection, reminding us of our shared human experiences, albeit through whimsical narratives. The enduring appeal of such characters speaks to an inherent longing to connect, to see ourselves reflected in the world around us, no matter how fantastical it may be.

In conclusion, anthropomorphism unveils itself as a kaleidoscopic tapestry woven from the threads of history, philosophy, and cultural expression. Its trajectory from ancient animism to modern storytelling underscores a fundamental aspect of the human condition: our incessant quest for connection and understanding. The anthropomorphic lens, rich with metaphorical potency, challenges us to reconsider our place in the cosmos, inviting us to embrace the myriad forms of consciousness that populate our shared reality. In a world teeming with complexity, the simple act of attributing human qualities to the non-human may, paradoxically, be the most profound reflection of our shared humanity.