Anthropomorphism, the attribution of human traits, emotions, or intentions to non-human entities, pervades our daily existence. From inanimate objects adorned with faces to beloved plush toys that become confidants, this phenomenon reveals a poignant truth: we, as humans, often perceive and engage with the world around us as if it were imbued with the characteristics of our own species. The compelling fusion of anthropomorphism and object attachment elucidates why we form profound connections with things in our lives that seem to resonate with our own humanity.

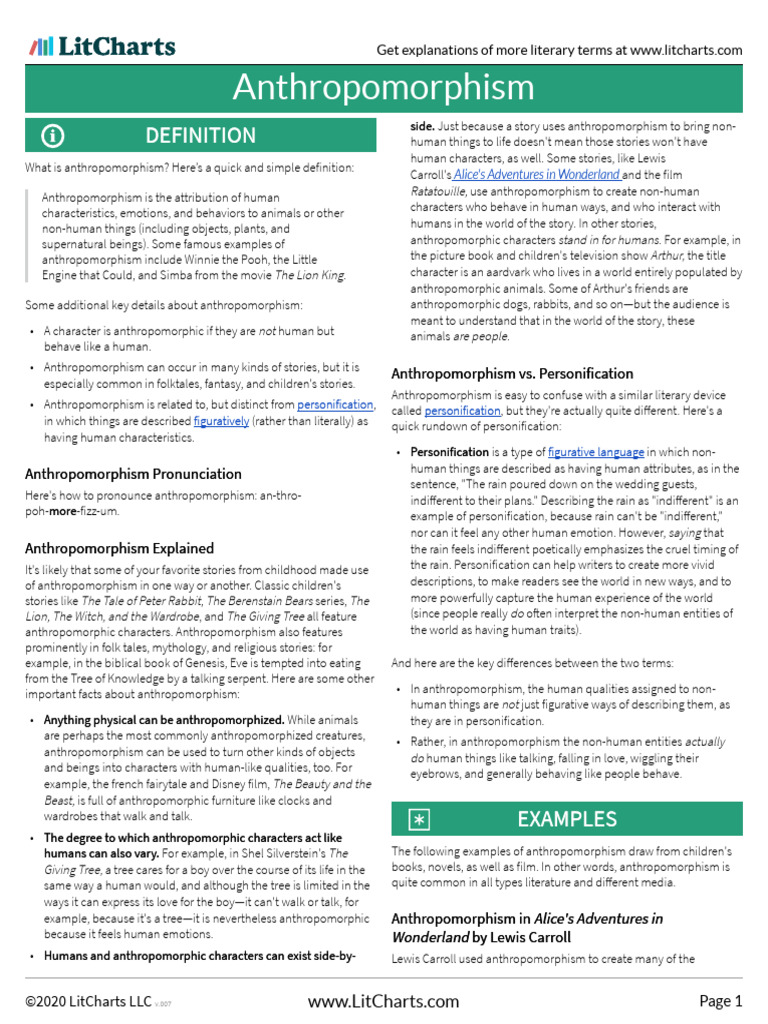

The genesis of anthropomorphism can be traced back to humanity’s inherent need for connection. Psychological studies suggest that this tendency is rooted in our primordial instincts evolved through millennia. Our ancestors, surrounded by a chaotic and often perilous environment, relied heavily on interpersonal relationships for survival. Those who anthropomorphized their surroundings—seeing life in stones, trees, and animals—might have benefited from a heightened sense of empathy and awareness of their environment. This psychological predisposition persists today, influencing our perceptions and interactions with various aspects of life.

Consider how children relate to their toys. A teddy bear or a doll often transcends its mere material form, becoming a companion who listens without judgment and comforts in times of distress. These objects transform into vessels of feelings, harboring secrets and memories that serve not only as playthings but as vital emotional support systems. As adults, we might find nostalgia for these interactions, hinting at still-active attachment patterns that stem from childhood. The beloved toy that accompanied us through formative years often finds a place of honor on a shelf, symbolizing a tangible connection to innocence, creativity, and comfort.

The fascinating interplay between anthropomorphism and object attachment extends into the realm of technology. With the advent of digital assistants and artificial intelligence, we are increasingly prone to ascribing personality traits to devices designed solely for functionality. Voice-activated speakers can be imbued with charming personalities through the modulation of their digital voices, leading users to forge emotional bonds with what are essentially advanced computer systems. This is indicative of a larger trend where individuals seek solace and familiarity in the phantasmagoria of technology. The slight human-like quirks of these devices often provide users with an illusion of companionship, echoing a deep-seated need for connection amid an ever-competitive digital landscape.

However, this phenomenon invites the question: why do we develop such profound attachments to objects? The concept of object attachment hinges on the idea that the objects we cherish can encapsulate significant aspects of our identity. Consider a cherished family heirloom—a simple object that transcends its material value. It represents lineage, family history, and memories infused with love and affection. Thus, our attachment is not merely to the object itself but to the rich tapestry of experiences and emotions it carries. This relationship often evolves into a form of nostalgia, where memories associated with the object become an integral part of who we are.

Culturally, anthropomorphism can serve as a bridge between our abstract understandings and the complexities of human experience. Across different societies, animals and objects often symbolize traits and values. For instance, the lion epitomizes courage, while the owl embodies wisdom. This anthropomorphic representation allows individuals to navigate complex social and moral landscapes. By ascribing human traits to these symbols, people can better comprehend and communicate intricate ideas, fostering a shared understanding within their cultural milieu.

Moreover, the dynamic of anthropomorphism fosters empathy, an essential component of human interaction. When we perceive traits of ourselves in others—be they fellow humans or anthropomorphized objects—we are more inclined to empathize with their experiences. The emotional resonance of shared traits builds a connection, enhancing our ability to relate and support one another. In a world marked by increasing polarization and fragmentation, the practice of viewing objects and beings through an anthropomorphic lens may serve as a unifying mechanism that mitigates conflict.

The attachment to objects has manifested itself in surprising ways in contemporary society. The phenomenon of “objectophilia,” where individuals feel profound emotional connections to inanimate objects, showcases the extreme lengths of this attachment spectrum. This raises poignant inquiries regarding the nature of love and connection in a post-modern context. Is it possible to establish genuine bonds with things devoid of consciousness? Many would argue yes, as the emotional fulfillment derived from these connections is as real as any relationship.

Our proclivity for anthropomorphism and attachment propels us toward a deeper understanding of ourselves. It illuminates our desires for connection, empathy, and meaning—struggles that resonate across time and space. This innate behavior resonates strongly in a technologically saturated universe, as we seek to bridge the chasm between isolation and intimacy.

In conclusion, the intertwined relationship of anthropomorphism and object attachment is a testimony to the complexities of human emotions. It reveals fundamental truths about our quest for connection and understanding in a rapidly changing world. By embracing these relationships, we acknowledge the emotional landscape that shapes our experiences, illuminating the often-overlooked beauty found within our bonds with the objects that punctuate our lives. Whether they are toys from our childhood, beloved gadgets, or generational heirlooms, these attachments remind us of our shared humanity in a world brimming with the inanimate—inviting us to reflect, connect, and nurture those unseen threads that bind us to our surroundings.