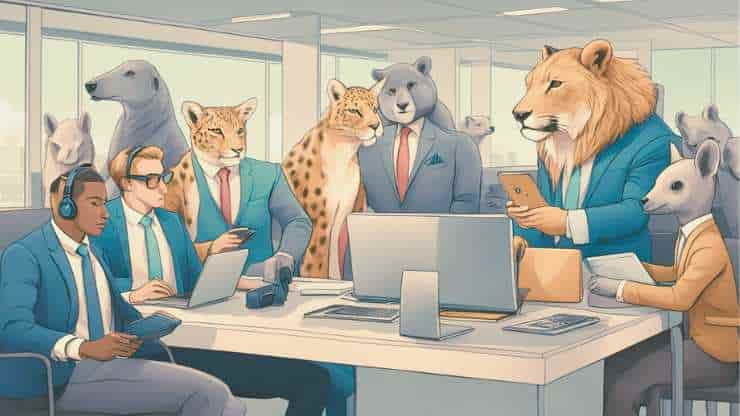

The world we inhabit is brimming with a cacophony of creatures, each enclosed in their own labyrinthine consciousness. When we encounter these beings, we often find ourselves infusing them with our own thoughts, emotions, and motivations—a phenomenon known as anthropomorphism. This inclination to attribute human traits to animals is not merely an endearing quirk of our psyche; it encapsulates a profound interstice between our understanding of ourselves and the natural world. The intricate dance of mental state attribution invites us to peer beneath the fur, feathers, and scales of our fellow inhabitants. What might they think? How do they perceive their realities? In this exploration, we will delve into the captivating realm of anthropomorphism and the complexities of ascribing mental states to non-human beings.

Anthropomorphism springs from a fundamental human desire to connect. It acts as a bridge, allowing us to traverse the chasm that separates our human experience from the enigmatic lives of animals. This phenomenon manifests in various contexts—literature, art, even in marketing. Think of beloved characters like Winnie the Pooh or the myriad of animated films that present animals with rich inner lives and relatable dilemmas. Yet, beyond the realm of fiction, anthropomorphism can influence our perception of animals in the wild, shaping our interactions and policies regarding their treatment and conservation.

But why do we find comfort in attributing emotions to creatures so distinctly different from ourselves? The concept of anthropomorphism can be likened to the age-old philosophy of solipsism—the idea that only one’s own mind is sure to exist. Just as solipsism invites a solitary narrative, anthropomorphism offers a shared narrative. It enables us to project our sentiments onto the animal kingdom, forging symbolic alliances with beings that evoke both empathy and curiosity. When we see a dog wag its tail, we interpret its exuberance as joy; when we watch a cat knead with its paws, we ascribe it to comfort and contentment. In essence, we are participating in a cognitive dance, entwining our perceptions with the essence of another species.

Yet, this tendency is a double-edged sword. While anthropomorphism can foster compassion and inspire conservation efforts, it can also lead to misinterpretations of animal behavior and welfare needs. For instance, a mother dog caring for her pups is often seen as demonstrating parental love, yet, from a biological standpoint, her actions are instinctual—rooted in survival rather than emotional attachment. When we misjudge animal behavior through a human lens, we risk implementing misguided policies or interventions that could harm rather than aid them.

To navigate the nuances of mental state attribution, one must embark on a journey of understanding—an unrelenting quest to discern the veritable realities that lie behind animal behaviors. Researchers in the fields of ethology and cognitive psychology are tirelessly unraveling this curious tapestry. They postulate that many species possess intricate cognitive capacities, displaying emotions like joy, fear, and even grief. The renowned study of elephants mourning their dead exemplifies this phenomenon, as these majestic mammals exhibit behaviors that suggest a deep-rooted sense of loss. Such observations challenge us to reconsider our definitions of consciousness and sentience—concepts we often reserve exclusively for humankind.

In delving deeper, one encounters the fascinating concept of theory of mind—the ability to attribute mental states to oneself and others. This cognitive leap is fundamental for sophisticated social interactions. While humans exhibit a nuanced understanding of theory of mind at an early age, the presence of this ability in other species is an area of deep inquiry. Crows, for instance, demonstrate problem-solving skills that suggest a rudimentary form of this cognitive faculty. Their capacity to plan for future events and manipulate situations to their advantage hints at a complex understanding of their environment—an understanding that is both instinctive and reflective.

Moreover, this discourse intertwines with the realm of ethics. If, as research indicates, animals are capable of experiencing emotions analogous to our own, our moral obligations toward them come into sharp focus. The philosophical musings of animal rights advocates provoke us to question: Are we justified in exploiting creatures for our benefit, assuming they exist solely in servitude to humankind? By recognizing the depth of animal sentience, we may be compelled to reevaluate our hierarchical view of species and consider the inherent dignity of all living beings.

Within this vibrant tapestry of anthropomorphism and mental state attribution lies an inescapable reflection of our human experience. The way we perceive and interpret animal behavior serves not only as a mirror of our understanding of the animal kingdom but also as a lens through which we can examine our own humanity. As we continue to dance with the delicate balance of empathy and cognition, we uncover a burgeoning realization: to truly comprehend animals, we must learn to appreciate the limitations of our anthropocentric perspectives.

As we draw the curtains on this exploration, it is imperative to acknowledge the captivating allure of the unknown. The more we strive to understand the thoughts and feelings of other species, the more we awaken to the mysterious beauty of existence itself. In our quest to relate to our fellow beings, we might just discover the essence of our shared journey through this remarkable tapestry of life—a journey defined by a symphonic interplay of hearts and minds, bridging the gap between the human and the non-human realms.