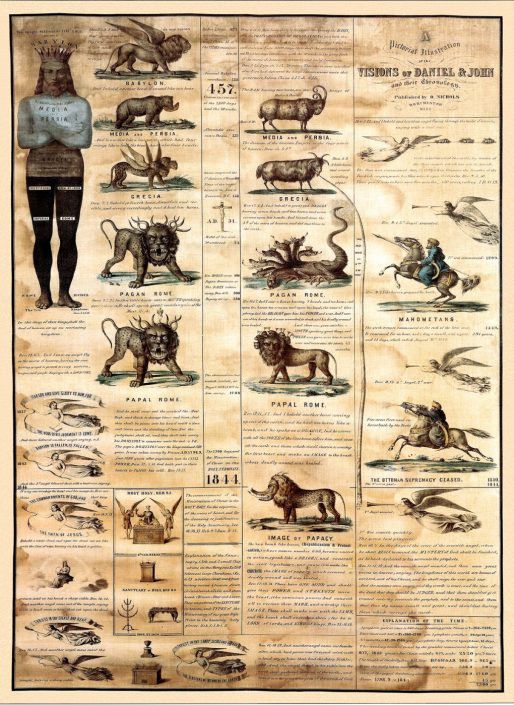

Anthropomorphism, the attribution of human characteristics to non-human entities, has intrigued theologians, philosophers, and scholars for centuries. In the context of Islam, the implications of anthropomorphic interpretations of the Divine raise significant theological questions and foster extensive debate. This article elucidates the multifaceted nature of anthropomorphism in Islam, exploring its textual roots, theological ramifications, and the divergent viewpoints among scholarly interpretations.

At its core, anthropomorphism in Islam involves the understanding of God’s attributes through a human lens. One of the most intricate bases for this belief lies within the Quran itself, where various verses seemingly ascribe human-like qualities to God. For instance, terms such as “hand” or “face” when referring to God have prompted extensive commentary and exposition. These expressions are often interpreted within the context of divine transcendence, suggesting that while God may possess attributes described in human terms, His essence remains utterly beyond human comprehension.

To navigate the landscape of anthropomorphism in Islam, it is essential to consider the theological substratum of the Quran. The text is a compendium of revelations reported to the Prophet Muhammad, and its language oscillates between abstraction and personification. The anthropomorphic attributes, when taken literally, could lead to a misunderstanding of God’s nature, an idea vehemently opposed by many Islamic scholars who favor an allegorical interpretation.

One of the pivotal discussions surrounding the theme of anthropomorphism in Islam is the theological doctrine of Tawhid, or the oneness of God. This principle posits that God is unique, without partner or equal. The challenge arises when anthropomorphic terms are interpreted in a manner that may suggest a duality in God’s nature, conflicting with the foundational tenets of Tawhid. Scholars have distinguished between a ‘literalist’ approach and a ‘metaphorical’ approach to these verses, with the latter often prevailing in traditional Islamic scholarship.

Among the various schools of thought, the Ash’ari and Maturidi schools of Kalam (Islamic theology) argue that God’s attributes, while mentioned in anthropomorphic terms, do not resemble human attributes. This rhetoric seeks to preserve the transcendental nature of God while allowing for a deeper engagement with scriptural texts. In contrast, some early anthropomorphic sects, such as the Hashwiyyah, adopted a more literalist stance, arguing for the affirmation of God’s physical attributes.

This debate extends to modern contexts, where the rise of secular interpretations of scripture has further complicated traditional understandings. Contemporary scholars seek to reconcile ancient texts with modern philosophical inquiries about the nature of God, often invoking anthropomorphism as a means of relating the divine to human experiences. This juxtaposition prompts reflection on the relevance of divine characteristics in an age skeptical of supernatural claims.

Moreover, the discourse on anthropomorphism encompasses diverse expressions within Islamic spirituality. Sufism, for instance, engages with anthropomorphic language through a mystical lens, emphasizing a personal relationship with the Divine. Sufi poets like Rumi and Al-Ghazali utilized anthropomorphic imagery to elucidate spiritual truths, inviting followers to experience the Divine presence in a relatable manner. Such perspectives highlight the emotional and psychological dimensions of faith, accentuating that the humanization of God may serve as a bridge to deeper spiritual understanding.

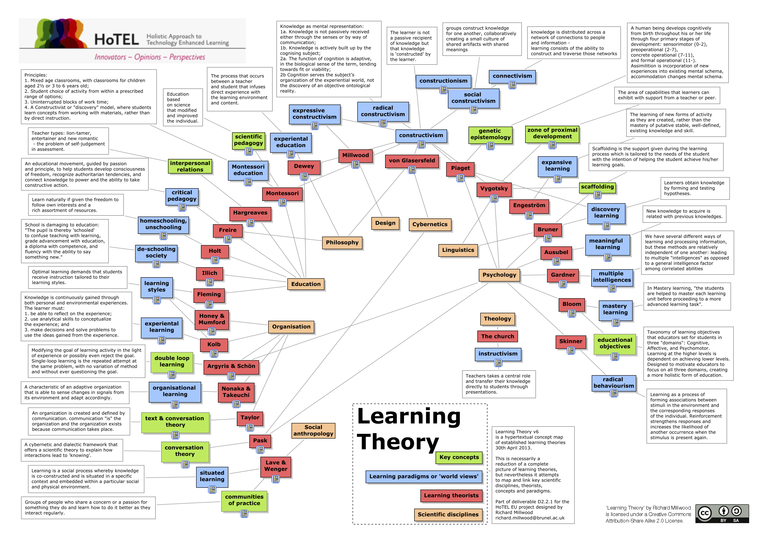

Despite its theological complexities, anthropomorphism can indeed serve as a pedagogical tool within Islamic teachings. The use of relatable imagery facilitates understanding, especially among children and lay followers. Religious educators often employ stories infused with anthropomorphic elements to impart moral lessons, emphasizing mercy, compassion, and justice—qualities ascribed to God that resonate within human experience.

Addressing the implications of anthropomorphism also necessitates an examination of its potential pitfalls. A literal interpretation can inadvertently lead to a type of idolatry—where attributes of the divine might be overly humanized, undermining God’s transcendental nature. Moreover, such interpretations can sow divisions among differing sects and schools of thought, as adherents espouse varying understandings of divine qualities and their implications for worship.

In conclusion, anthropomorphism in Islam presents a layered and nuanced tapestry of belief that reflects the struggles of humanity in grasping the ineffable nature of the Divine. From its textual origins in the Quran to its various interpretations by scholars and practitioners, the discourse embodies the tension between transcendence and immanence. With a thoughtful approach that respects the rich theological heritage of Islam, believers and scholars alike can continue to explore and appreciate the depth of divine representation in both ancient texts and contemporary faith experiences.

The journey through anthropomorphism in Islam illuminates the human quest for meaning, connection, and understanding of the divine. It prompts critical reflection and invites believers to engage with the complexities of faith, transcending simplistic interpretations to embrace a more profound spiritual engagement with the Divine. As such, the exploration of anthropomorphism remains an essential component of Islamic theology and spirituality, resonating deeply within the hearts and minds of believers.