Anthropomorphism, the artistic and philosophical practice of attributing human-like qualities and emotions to non-human entities—ranging from animals to inanimate objects—holds a particularly profound resonance within Indigenous belief systems. These societies often merge the natural and the supernatural, crafting intricate tapestries of spirituality where nature is not merely a backdrop, but an active participant in the cosmic drama of existence. This phenomenon fosters a deep-rooted connection to the land and its myriad inhabitants, allowing for a symbiotic relationship that governs the lives and cultures of Indigenous peoples.

The concept of anthropomorphism in Indigenous cultures is beautifully reflected through the narratives and mythologies that permeate their traditions. For instance, animals often become the vessels of wisdom, embodying human traits and behaviors that are deeply instructional. The coyote, revered in many Native American traditions, is often depicted as a trickster—a being that embodies both cunning and folly. Through tales of the coyote, moral lessons are imparted, with the creature serving as a reminder of the complexities and contradictions inherent in human nature itself. This fluidity between human and animal characteristics engenders a rich storytelling tradition that captivates and instructs, inviting listeners to reflect on their own lives.

In Indigenous belief systems, every element of the natural world possesses a spirit or essence that is intrinsically linked to its material form. Mountains may be seen as ancient guardians, rivers as life-giving veins of the earth, and trees as wise, old sages sharing stories with the winds. Such perceptions encourage reverence and stewardship, urging communities to protect their natural surroundings and forge sustainable paths. Here, anthropomorphism transcends mere characterization, evolving into a spiritual dialogue wherein human beings engage with the environment as equals rather than dominators.

One cannot overlook the significance of totemic representation in this context. Totems serve as emblematic embodiments of clans, families, or individuals within Indigenous cultures, frequently deriving from animals or natural phenomena imbued with anthropomorphic traits. The bear, for example, symbolizes strength, courage, and introspection. It is not merely a creature of flesh and bone but rather a spirit guide, embodying the traits desired by the community it represents. This relationship imbues the bear with a kind of sacredness—one that dictates not only behavior but also cultural practices surrounding hunting and respect for the harvest.

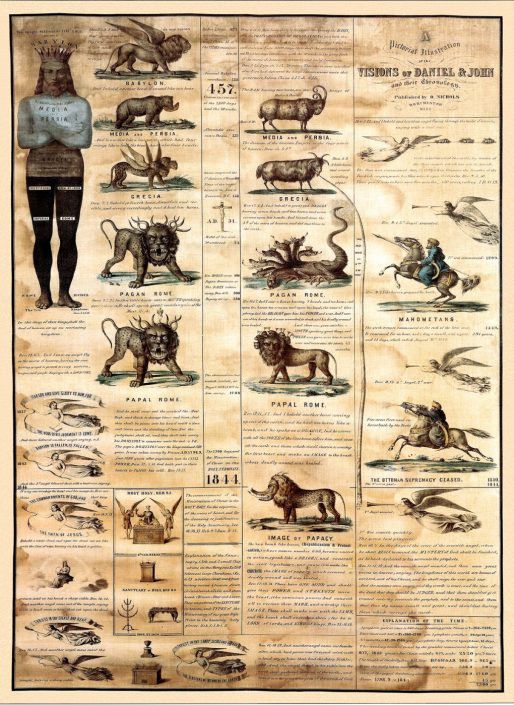

Additionally, the anthropomorphic qualities attributed to deities within various Indigenous pantheons amplify the intricate fusion of the human and the divine. Deities often reflect human emotions—love, jealousy, wrath—while simultaneously possessing control over natural forces and phenomena. In this manner, the divine is rendered relatable, making it easier for devotees to comprehend and navigate the complexities of their existence. Elaborate mythologies thus arise, where the trials and tribulations of these deities mirror human struggles, fostering a deep sense of connection between the sacred and the mundane.

The use of anthropomorphism serves to underscore the overarching cosmological view that permeates Indigenous cultures: everything is interrelated, and the boundaries between human, animal, and spiritual realms are often fluid. This worldview creates a rich tapestry of symbiotic relationships, where the actions of one affect the collective. For example, the overhunting of a species may not simply be a matter of economics; it can be viewed as a disruption of balance, offending the spirits and leading to dire consequences. This belief creates a deep-rooted ethic of care and reciprocity towards nature, reinforcing the idea that humans are but one thread in the vast web of life.

Perhaps the most compelling aspect of anthropomorphism in Indigenous belief systems is how it nurtures a profound sense of identity and belonging. Through the stories they tell and the relationships they foster, individuals find meaning and purpose in their connectedness to the land and its beings. When families gather to recount tales of their ancestors’ interactions with the natural world, the very act of storytelling reinforces cultural continuity, imbuing communal bonds with depth and significance.

Moreover, in an increasingly urbanized world, the anthropomorphic narratives embedded within Indigenous belief systems take on an even more poignant relevancy. As disconnection from nature becomes a prevalent phenomenon, these teachings offer a timely reminder of the importance of cultural heritage and environmental stewardship. They echo a call to rediscover the intricate relationships we share with the world around us, pushing against the tide of materialism and separation.

Ultimately, the anthropomorphism found in Indigenous belief systems illuminates the enduring capacity of storytelling as a mode of understanding and engaging with the universe. By weaving together human traits with the essence of nature, these narratives provide not only explanations but also ethical frameworks that privilege harmony over domination. Such works echo through generations, concurrently shaping individual identities and molding communal values, inviting us all to reflect on our interconnectedness and the legacy we leave for future generations.

In essence, anthropomorphism within Indigenous cultures serves as a vibrant lens through which we can examine the dimensions of life, urging profound respect for the world we inhabit and reminding us of the timeless wisdom that exists even within the natural world. The blend of the human experience with the broader tapestry of life offers insights that resonate at the core of existence, highlighting the beauty in our shared journey.