Anthropomorphism, a captivating concept that has intrigued scholars, writers, and artists alike, invites us to ponder a profound question: What if the inanimate, the abstract, and even the divine could speak in human tongues? In a world where animals converse with humans and objects wield emotions, where do we draw the line between personification and ideological representation? In this exploration, we delve deep into the etymology, meanings, and linguistic evolution of anthropomorphism, revealing its rich tapestry woven through time and ideas.

The term “anthropomorphism” traces its roots back to the Greek words “anthropos,” meaning human, and “morphe,” meaning form or shape. This compound originated in the context of the ancient Greek stories where gods exhibited distinctly human traits, reflecting the human condition and desires. A quintessential example is Zeus, whose lusts and jealousies illustrate divine characteristics through human lenses. The etymological origins of anthropomorphism reveal a historical inclination to understand the universe through the familiar—the human experience.

In the broader context of philosophy and literature, anthropomorphism serves not merely as a rhetorical device but as a foundational element that shapes our understanding of nature, morality, and existence itself. By attributing human traits to non-human entities, we enhance relatability and facilitate emotional connections. For instance, George Orwell’s “Animal Farm” employs anthropomorphism to demonstrate the dynamics of power and corruption, where pigs, endowed with human-like qualities, serve as allegories for political figures. Herein lies the challenge: does anthropomorphism obscure reality, or does it elucidate complex themes within human society?

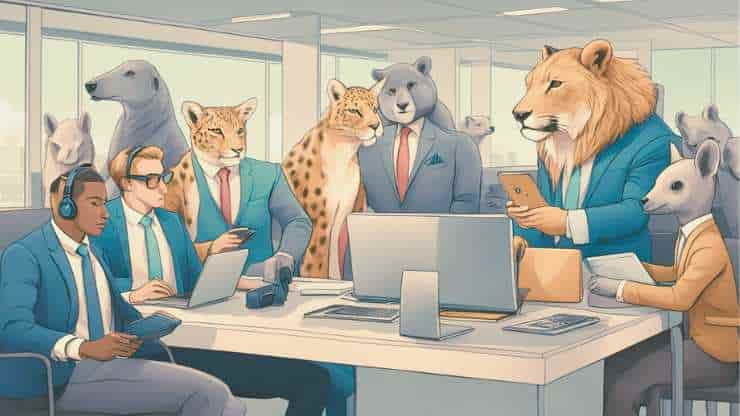

From ancient mythology to modern storytelling, forms of anthropomorphism abound. In Aesop’s Fables, animals act with a degree of intellect and morality, driving home lessons that resonate with human readers. The Tortoise and the Hare underscores perseverance versus hubris, employing anthropomorphized creatures to embody these virtues. This literary tradition has morphed over centuries, as we witness characters like Winnie the Pooh and the various denizens of animated films like “Zootopia.” Such manifestations evoke a spectrum of emotions, allowing audiences, particularly children, to grapple with abstract concepts like friendship, loyalty, and fear.

Anthropomorphism also plays a crucial role in religion and spirituality. Ancient deities were often depicted with human attributes, ensuring that their followers could connect personally with the divine. Consider the Hindu pantheon, where gods such as Vishnu and Shiva embody human emotions and moral struggles, making the divine more accessible to the believer. This embodiment invites adherents into a narrative where they can envisage divine intervention in their lives. The intersection of faith and anthropomorphism elevates the human experience to a mythical plane, yet it also raises significant discussions about the nature of divinity. Does attributing human characteristics to gods simplify the divine, or does it deepen our understanding of the sacred?

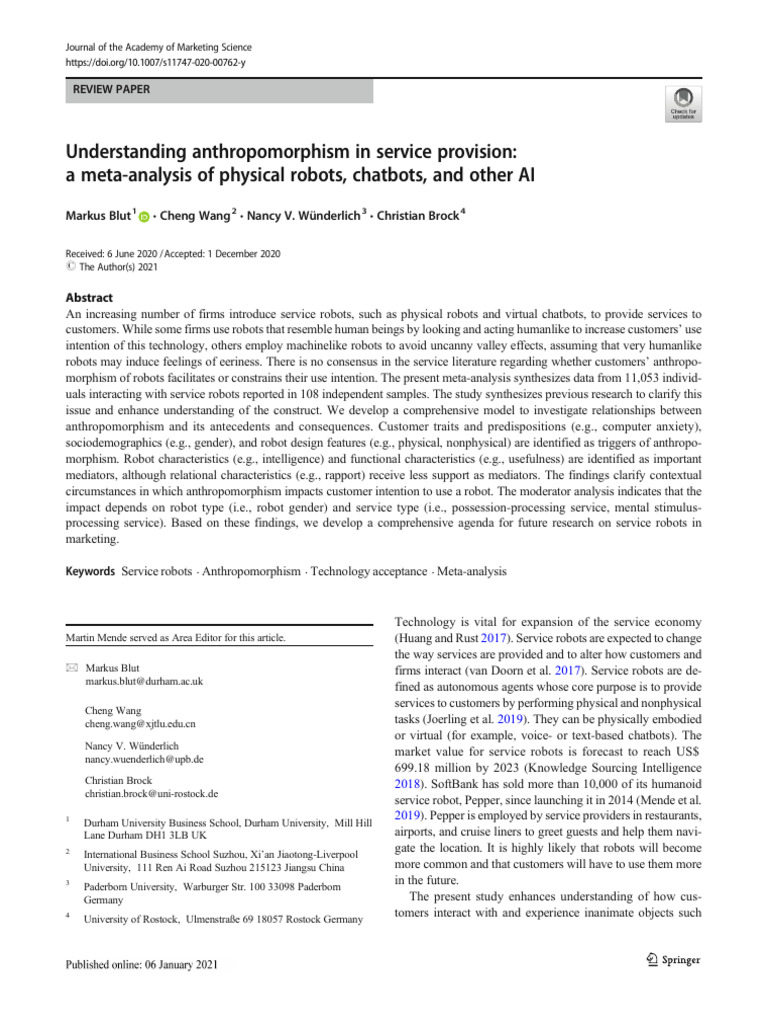

As we navigate through history, it becomes apparent that the application of anthropomorphism oscillates between artistic expression and philosophical exploration. The Renaissance brought a resurgence of interest in anthropomorphic imagery, manifesting in art that humanized biblical stories, allowing viewers to evolve their connection with faith. Additionally, contemporary literature continues to embrace this device, pushing boundaries and posing even more consequential questions: can machines become characters in a story? As artificial intelligence grows more sophisticated, we find ourselves anthropomorphizing technology, attributing emotions and intentions to algorithms and applications. This leads to the inevitable inquiry: what does it mean when we begin to assign human characteristics to our creations?

Language itself is not insulated from the effects of anthropomorphism. Idioms such as “the angry sky” or “the smiling sun” reflect a linguistic tendency to invoke human characteristics to describe weather patterns and natural phenomena. This use of personification invites a deeper connection with the environment, allowing speakers to communicate experiences and evoke empathy for elements beyond human control. Such linguistic tendencies encourage artistry within everyday communication, enriching interactions and evoking emotional responses.

The evolution of anthropomorphism also intersects with the fields of psychology and sociology. Human beings have an inherent proclivity to seek connection in everything around them, a trait known as “pareidolia.” This inclination often drives us to ascribe human-like qualities to pets, household items, or even natural occurrences. The implications stretch beyond mere fascination; they underscore a psychological need for companionship and understanding in an often confusing universe. Personality-driven marketing, particularly in consumer culture, harnesses anthropomorphism for branding. Cartoon mascots designed to be relatable foster loyalty and trust, employing friendly personas to connect with consumers.

Yet, in a society that increasingly embraces anthropomorphic attributes, a paradox arises. As we imprint human characteristics on animals, objects, and technology, we also risk oversimplifying life’s complexities. Does this encourage an ethical detachment from the beings we project humanity upon? For example, does viewing animals merely as companions with human traits diminish our responsibility to protect wildlife and their habitats? This discourse invites us to reconsider our symbiotic relationship with nature and technology.

In conclusion, anthropomorphism encapsulates a profound interplay between language, culture, and perception. Rooted in etymological history, its journey reflects the continuous evolution of human thought. Whether through the whimsical tales of literature, the sacred narratives of religious texts, or the intricate dialogues of contemporary society, the essence of anthropomorphism transcends mere artistic flourish—serving as a mirror that reflects the human condition back to us. As we grapple with the magical and the rational, we stand challenged to discern the boundaries of our anthropocentric perspectives. In a world where toys may exhibit feelings and inanimate beings tell stories, the question remains: what truths about ourselves do we uncover when we breathe life into the lifeless?